Thanks for joining me for the 21st issue of the Golden Stats Warrior, a newsletter for data-based insights about the Bay Area. If this is your first time reading, welcome! If you haven’t signed up yet, you can do that here. I am grateful for your support.

This is the first Golden Stats Warrior guest post. I am thrilled that it is by my friend and former colleague Youyou Zhou. Youyou is one of the most thoughtful and talented journalists I know. Born in China, she has lived in the US for the past 10 years, and much of her work focuses on immigration across the world. I asked her to write a piece about Chinese immigration to the Bay Area. Enjoy! (If you are interested in writing a guest post, please reach out to me.)

I have quite a few Chinese friends in the Bay Area. They generally live in the South Bay and work for a tech company in Silicon Valley neighborhood. None of them live in San Francisco .

Yet, according to the 2018 American Community Survey, the highest density of Chinese immigrants nationwide can be found in San Francisco County. They make up over 18% of the population.

There’s a clear distinction between the Chinese tech workers in the South Bay that I know, and those in the downtown area. The differences are a result of the rather twisted history of Chinese immigration to the US. The experience of working as a software engineer in the tech sector, though familiar to new immigrants like me and my friends, is far from the complete story. (I define Chinese immigrants as people either born in China or who speak Chinese at home.)

San Francisco was one of the first destinations for Chinese immigrants to the US. Unlike the greater New York metro area’s Chinese immigrants, almost all of whom came after the 1960s, the Bay Area experienced two large waves of immigration from China. (I am using the nine-county definition of the Bay Area throughout this article.)

The first wave of immigrants to the Bay Area from China came to work in gold mines starting in the 1850s. They later became laborers, working in factories, on railroads and farmlands. This wave of immigration was disrupted by the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, a targeted discriminatory policy to prevent immigration from China. Chinese immigrants fell almost to zero in the first half of the 20th century (though many descendants of the first wave continued to live in the region). After the policy was abolished in the mid-1950s, immigration picked up again.

The front of a postcard purchased at a flea market in Woodstock, NY depicts a shoemaker in San Francisco’s Chinatown, as adapted from the 1907 book "On the road of a thousand wonders"

Perhaps the most consistent feature of Chinese immigrants to the Bay Area is that they are always desperate to work. Some come to increase their fortune, others to support their families back home. Just take a look at the jobs Chinese immigrants took at any historical point, and one will understand their story.

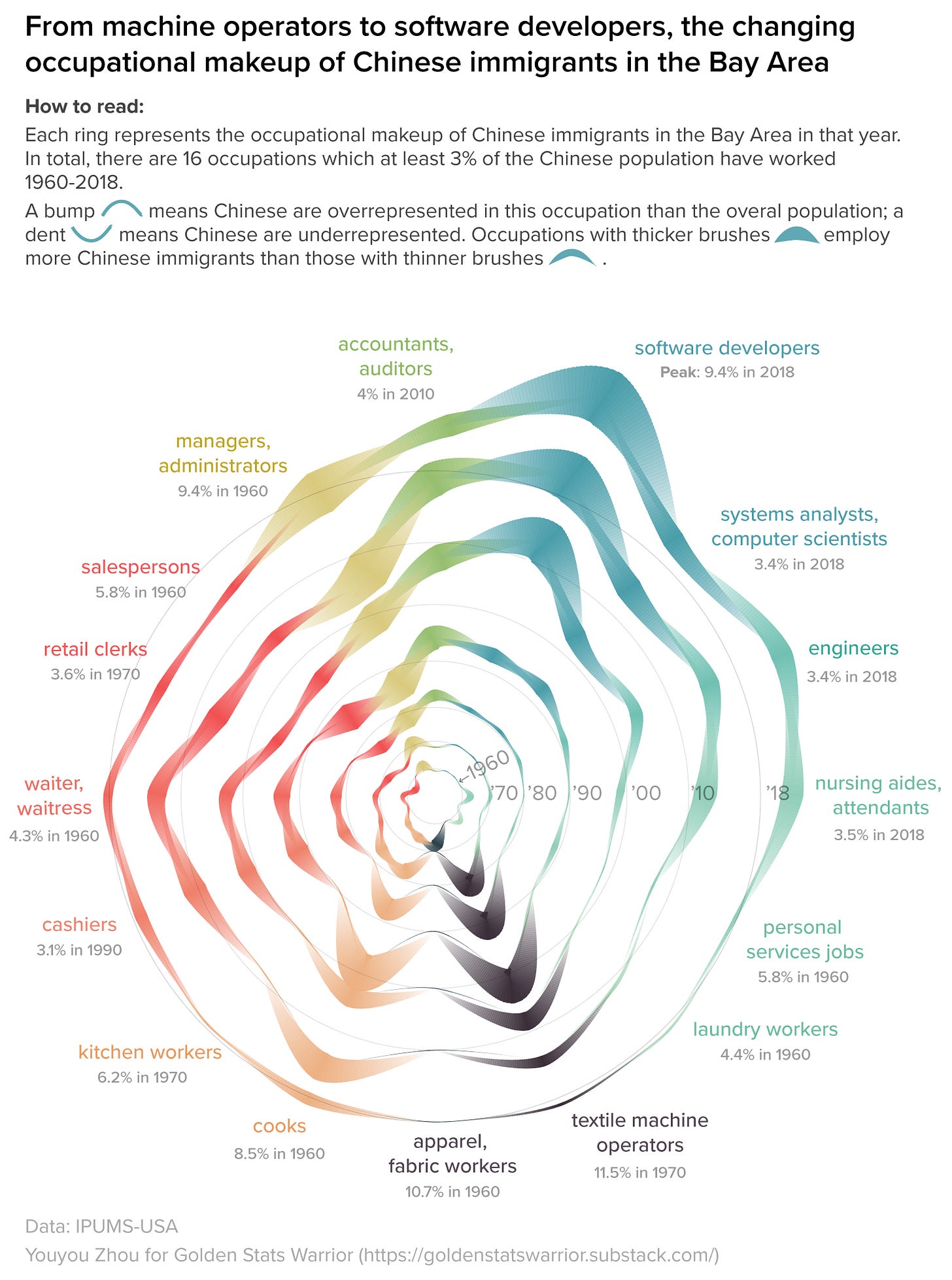

Many of the Chinese immigrants in the first half of the twentieth century were self-employed because they couldn't find waged jobs due to the Chinese Exclusion Act. As a result, they were unusually likely to open up laundries and restaurants. In 1960, 8.5% of Chinese immigrants in the Bay Area were cooks, 5.5% kitchen workers, 4.3% waiters and waitresses, and 4.4% laundry workers. They were also over indexed in low-paying jobs, like fabric workers and nursing aids.

Between 1970 and 2000, they were unusually likely to be machine operators, cooks, and kitchen workers. While only 0.3% of the Bay Area non-Chinese population worked as textile sewing machine operators in 1970, 11.5% of Chinese worked in this profession.

Starting from the internet boom around 2000, Chinese immigrants worked as engineers and programmers in higher proportions than the average Bay Area resident. Today, most Chinese immigrants can be found working in high-skilled, high-paying occupations such as programmers, managers, administrators, and accountants. For example, only about 0.3% of the population back in 1970 were computer software developers, Chinese or non-Chinese. That increased to 4.2% for non-Chinese in 2018, and about 9.4% for Chinese.

The shifts in occupational makeup is also evident when looking at the Bay Area’s counties. Chinese have gradually moved away from the downtown area into outer counties with other residents. Today you can find Chinese managers and executives in Marin, Contra Costa, and Sonoma; Chinese computer engineers in Alameda, San Mateo, Contra Costa, and Santa Clara. Most Chinese remaining in San Francisco today, however, still work in lower-income jobs.

From the gold rush, to the mid-twentieth century golden age of manufacturing, to the dot-com boom, Chinese immigrants have always worked more in the Bay Area’s rising industries than the general population. That is, perhaps, the story of immigrants in general: when the economy needs workers, it finds immigrants.

- Youyou Zhou

Bay Area media recommendations of the week

(This is Dan again.)

This week I want to recommend a book. Even if you never go fishing, you should still pick up Kirk Lombard’s The Sea Foragers Guide to the Northern California Coast. It is one of the most informative, funny and profound books I have read about the Bay Area.

At its most basic, the book is a guide to understanding the edible seafood of the Bay Area, and where and how you might catch them. But it is so much more. The book is full of lessons about ecology, local culture, and what makes for a good life. It also includes short stories and poems about specific fishes. The writing is beautiful.

Here is taste of Lombard’s irresistible prose, from a section on the sand dab: “Like almost all members of the flounder clan, the sand dab is deeply delicious. And yet its popularity seems to be restricted primarily to California—and more specifically to the area from Santa Barbara to San Francisco. Go to a fine seafood restaurant anywhere else in the United States and ask the chef when they will be getting sand dabs in, if you want to understand the very definition of a blank stare.”

Thanks to Daniel Wolfe for the recommendation.

(If you read or listened to something great about the Bay Area this week, please send it to me!)

Dan’s favorite things

The Visitacion Valley Greenway is one of the great hidden parks of the region. Located in the residential Visitacion Valley neighborhood in southeastern San Francisco, the Greenway is made up of six different block-length small public parks on land once owned by the city’s water department. The parks have gained a bit more fame recently as one of the first stops on the 17-mile Crosstown Trail, a hike that I highly recommend.

The Greenway has a special kind of urban magic. The little parks have winding paths, and surprising offshoots. It’s the kind of shared, calming space that is the best of urban architecture.

Thanks for your time, and see you in a couple weeks.

If you think a friend might enjoy this newsletter, please forward it along. You can follow me on Twitter at @dkopf or email me at dan.kopf@gmail.com

The Golden Stats Warrior logo was made by Jared Joiner, the best friend a nervous newsletter writer could have. Follow him @jnjoiner.