The Bay Area's history is in shipping. What about its future?

The big crane game

Thanks for joining me for the 28th issue of the Golden Stats Warrior, a newsletter for data-based insights about the Bay Area. If this is your first time reading, welcome! You can sign up here.

I want to acknowledge how challenging these last few weeks have been. If you are in need of a little hope, I suggest you watch the Oakland Symphony’s Virtual Inauguration Ball, which includes performances by arts groups across the Bay Area. The performances, particularly by the kids, help me believe the future is bright.

Welcome the giant cranes! In late December, three of the world’s tallest cranes entered the San Francisco Bay on their way to the Port of Oakland. At full stretch, the cranes reach more than 400 feet. Their long reach will allow the Port to handle cargo from ultra-large container ships. Bigger ships can carry more stuff, making the Port more efficient.

These cranes are part of the Bay Area’s long-running battle to maintain its status as a major shipping center. In the hyper-competitive shipping industry, ports need to constantly improve in order not to lose out to competitors. In the Port of Oakland’s case, this means convincing ships to dock in the Bay, rather than the ports of Long Beach, Los Angeles or Seattle.

The Port is a too often overlooked facet of Bay Area life. It is a source of good middle-class jobs and a boon to local manufacturers. It is also one of the region’s least accountable government agencies. This week’s newsletter is dedicated to the past, present, and future of the Bay Area’s first great industry. A story in five charts and a map.

The Port of Oakland is the eighth biggest in the US

If you head to the Port of Oakland, located on the western most portion of city of Oakland, you are bound to see heaps of huge containers stacked on top of one another. These containers are an under appreciated key to globalization. The move from simply stuffing goods inside ships to putting them in stacked containers revolutionized shipping and made global trade more efficient.

Oakland was actually at the center of the container revolution. It was the first port on the West Coast of the US to build terminals for container ships, in part to serve the Vietnam War effort. (Check out the excellent Containers podcast to learn more about this history.)

In 2019, Oakland’s port was the eight busiest in the US. The equivalent of 2.5 million 20x8x8 feet containers came in and out of the port. There has been a small dip in volumes in 2020 due to the pandemic, but the Port is expected to rebound in 2021.

How come the Port’s not in San Francisco?

The original reason for San Francisco’s very existence as a major city was its port. The area near today’s Embarcadero was an excellent natural harbor, and the perfect place for trade after the Gold Rush in 1849.

Over the 20th century, San Francisco lost its status as the Bay Area’s major port to Oakland for two main reasons. One, manufacturing left the city. As the city got richer, real estate for production plants near the port got more expensive. This meant trucks transporting good from ships to manufacturers were often stuck in San Francisco traffic. Two, when container shipping arrived on the scene in 1960s, large investments in money and land were needed for ports to accommodate containers. It made sense to make those investments in still spacious Oakland, but not in dense San Francisco, which was already moving to a services based economy.

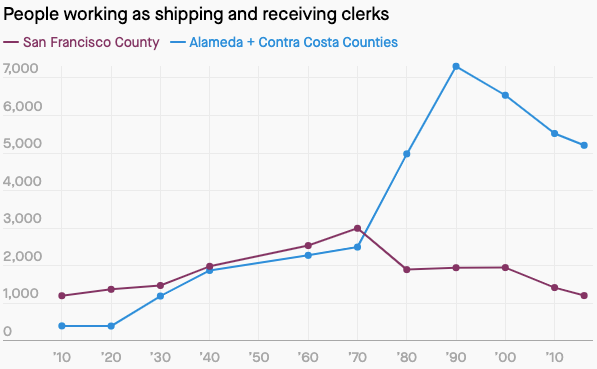

The chart below shows this change through the number of people in San Francisco working as “shipping and receiving” clerks, versus those doing that job in the East Bay, according to US Census data. The major use of San Francisco port’s today is for cruise ships.

How Oakland lost to LA

In the late 1960s, the Port of Oakland was the second busiest container port in the world. Today, it’s not even in the top 100. Although the Port of Oakland did get busier over the last 50 years, it grew much more slowly than competitors like Los Angeles and Long Beach. The chart below shows Oakland’s growth compared to LA and New York using data from the American Association of Port Authorities.

In a report for the public policy organization SPUR, my friend Jennifer Warburg explains what happened:

Essentially, Oakland has lost the size wars to Southern California’s maritime ports. L.A. and Long Beach together handle seven times more cargo volume than Oakland. These ports have benefitted from economies of scale and better rail connections to Midwestern and Eastern markets. L.A. and Long Beach have an intrinsic advantage in having 20 million customers within 100 miles, while the Port of Oakland has less than half the customer base. The nation’s railroads have invested heavily in access to L.A. and Long Beach, with negligible new investments for Oakland or the Pacific Northwest.

What actually comes in and out of the port?

Using data from the US Census, we can see exactly what is imported and exported from the Port of Oakland. The charts below show that a huge variety of goods are imported through the port, but the largest categories by customs value are electronics (like phones and computers), consumer goods (like furniture and toys), and cars. Most of these imports come from China and other countries in East Asia. The customs value of these imports was $31 billion in 2019. The categories in the chart below are the official categories used by the US government, so forgive me if they are a little confusing.

In contrast, the biggest exports are vegetables, meat and other food items. The majority of these products are headed to Asia, much of it grown in the California’s Central Valley. These exports were worth about $20 billion.

The Port is more than what you might think

What do the Oakland Airport, Jack London Square and Oakland’s ferry terminal have in common? They are all on land owned by the Port of Oakland. The Port of Oakland is not just a place where ships dock. It is an independent part of the Oakland city government governed by seven commissioners appointed by Oakland’s elected officials.

The Port controls about 20 miles of the waterfront, and acts as a landlord to the hotels, restaurants, airlines and shipping companies that use Port land. For example, the huge cranes were actually bought by the company SSA (Stevedoring Services of America), a tenant that helps load and unload ships.

The Port had revenues of almost $400 million in 2019, and the Port and its tenants employ around 30,000 people. Many of those jobs are the kind that the Bay Area doesn’t create much of anymore—middle-wage, skilled-labor positions that don’t require high levels of formal education.

Not everybody is happy about the Port’s relationship to the City. Critics believe that the Port’s independence leads to a lack of oversight. Pollution from the Port has had disastrous impacts on the health of West Oakland residents. People living in the historically Black neighborhood have higher rates of cancer and respiratory conditions due to traffic coming in and out of the Port.

It’s also questionable that unelected officials choose what to do with some of Oakland’s most valuable land. Those decisions may be based on what is best for the Port’s growth, but not what’s best for the city overall. The fast-tracked approval of a WalMart on Port land is an example of these oversight issues, according to a report from Reimagine Radio.

What’s the future of the Port?

In order to stay competitive, the Port is making a few major moves.

Perhaps the most important of these projects is a new “Seaport Logistics Center” located on the old Oakland Army Base. The $52 million Center will allow for logistics and distribution to be done within the port, cutting out truck trips to send containers to outside distribution centers. It will also be directly connected to a train depot. The Center should make it easier for the Port to handle perishable goods, like food and medicine, that need to be kept in cold storage.

The Port is also investing in infrastructure and software to reduce traffic for trucks picking up goods from the ships, while also keeping down pollution from those trucks. These investments include improving WiFi and building an app for drivers to more easily navigate the Port.

And, of course, there are those huge cranes.

Finally, there is one notable development on the Port which doesn’t involve shipping. The Oakland Athletics and the Port are now in exclusive negotiations over building a 35,000 person baseball stadium on Port land. Housing, offices and retail would be built around the stadium. The prospective stadium is controversial. People in the maritime industry worry it would create more traffic around the Port and limit future expansion. Others believe Oakland already has a perfectly good stadium.

Bay Area media recommendations of the week

Over the last several decades violent crime dropped dramatically in the Bay Area, as it has in the rest of the US. The reasons for the decline are not well understood, but it is a trend we can all be happy about. Unfortunately, this year saw a 35% rise in killings in the Bay Area, reports Megan Cassidy in the San Francisco Chronicle. (The rest of the US saw a similar rise.)

There were a total of 285 homicides in the Bay Area’s 15 largest cities in 2020, up from 210 in 2019, with the largest increases occurred in Oakland and Vallejo. Cassidy’s reporting suggests that Covid-19 was a primary contributor to the rise. The pandemic increased the stress and anxiety that can lead to violence. The pandemic also made violence-reduction programs like Ceasefire, which works to reduce gang-related homicides, harder to implement due to social distancing measures. Police behavior following the murder of George Floyd may have also caused homicides to spike. Research finds that officer-involved shootings often lead to an increase in community violence, as police are less likely to do their jobs in response to protests.

(Seen any great Bay Area media recently? Send it to me!)

Dan’s favorite things

Most people reading this newsletter will have crossed the Bay Bridge countless times by car. But have you walked it?

Starting in 2013, it has been possible to walk or bike across the eastern section of the bridge from Oakland to Yerba Buena Island. It’s a little noisy due to the nearby cars, but the 2.2 mile path is a glorious way to re-experience the Bridge. A trip back and forth across the bridge, and then a little relaxation at the recently opened pier at the foot of the bridge in Oakland makes for a perfect socially distanced afternoon. There is a steady incline from Oakland to Yerba Buena, but it is doable for most bikers.

One last thought. The western half of the bridge is named after former San Francisco mayor Willie Brown. The eastern half is not yet named. Why not use this opportunity to honor an East Bay great like Ida Louise Jackson?

Thanks for your time, and see you in a couple of weeks.

If you think a friend might enjoy this newsletter, please forward it along. You can follow me on Twitter at @dkopf or email me at dan.kopf@gmail.com. The Golden Stats Warrior logo was made by the great Jared Joiner, the best friend a newsletter writer could have. Follow him @jnjoiner. Also, thanks to my favorite plant lady Kanchan Gautam for copy editing this week.